Peacebuilding Tools for Resource Conflicts: What’s Needed, Available, but Little Known

Where international investment from powerful actors uses natural resources like water or land that sustain life for local people, conflict is a predictable result. We have seen those conflicts near a breaking point, but we have also seen firsthand how communities, companies, governments and institutions can build interpersonal relationships, trust, and overcome seemingly insurmountable barriers to come to agreement on a peaceful path forward.

In Mongolia, we have supported nomadic herders in a years long struggle to address conflict with a global mining company over the depletion of their pasture, water, and even air resources due to a massive mine they didn’t invite. In Mexico, we have supported Indigenous Chinanteco villages in their struggle with investors over a hydropower project that was slated to divert the entirety of a natural spring used for drinking water into a private, walled off channel. And in Myanmar, a fragile peace accord is threatened by a top down conservation project that risks displacing Indigenous Karen people from lands and forests they have stewarded for generations.

Particularly where local people are not served by the rule of law to assert their rights due to corruption or discrimination, communities often have few ways to be heard. When resource conflicts take place in the context of underlying active violence, in post-conflict environments of fragile peace where violent conflict is common, or in countries going through transitional justice processes, local people can face even greater risks of harm.

In this way, international investment can fuel violence: violence where corporations or governments abuse people dissenting at the local level, or creation of instability that risks violent conflict at a regional or even national level. We have seen both of these results of international investment at Accountability Counsel through our Communities program cases. Our Research program has documented 66 cases of violence against communities and retaliation that were raised by communities themselves in complaints to accountability offices tied to project investors.

Accountability Offices Provide Peacebuilding Options to Prevent Escalation

AC’s community training session in Mexico on OPIC’s Office of Accountability

So what have we learned? First, in Mexico, the conflict between the company and the community had the potential to get significantly worse if the early stages of construction continued. Community members were determined to stop harm from the Cerro de Oro Hydroelectric Project, even at potential personal risk, given the certain harm the project would bring as they lost access to drinking water and cultural resources, and as the safety of a dam they live below was threatened.

The communities filed a complaint to an accountability office tied to a project investor that resulted in a professional mediator bringing the parties together to talk. The project was suspended during the dialogue process, immediately lowering the risk of violence. Through the dispute resolution process that followed, the communities and the project company came to an agreement to end the project, protecting the communities’ water resources and sparing the company an almost-certain long term conflict and associated investment risks.

In this case, one of the many lessons for peacebuilding was the opportunity to turn to an accountability office dispute resolution process early on to steer problems towards a constructive solution and avoid escalation to potential violence. Accountability offices and the institutions in which they sit can play a vital role in moving a complaint quickly (particularly compared to litigation) and employing skilled mediators to address tensions through a professionally run process.

In Myanmar, the communities are using a compliance review function of an accountability office to raise grievances about a top-down conservation project with a decision making structure that violates the ceasefire agreement that ended armed conflict in the region. Here too, the project’s risks to peace have been abated so far because the implementing agency, UNDP Myanmar, suspended the project while the compliance review proceeds. Building peace in this case comes from work on all sides to listen to communities’ demands that their rights under peace accords and the rules of international institutions be respected.

Herder representative Namsrai at Oyu Tolgoi’s artificial spring

Peacebuilding Through Dialogue Can Facilitate Future Conflict-Resolution

In Mongolia, we have learned that even in the most extreme cases of competition for scarce resources, a dispute resolution process can play a vital role to address root causes of conflict and even set up a local, community-based grievance mechanism to resolve inevitable future conflicts. When the Oyu Tolgoi mine began operations in the Gobi Desert, it caused such intense competition for resources that it created conflict not only between local livestock herders and the mine, but also, over time, between herders themselves. As precious water and pasture resources grew scarce, disputes arose over access to shared wells and overcrowded pastures, at times becoming violent and even deadly.

Through an accountability office dispute resolution process, local herders had the opportunity to meet regularly with mining company and local government representatives. These parties used a collaborative and consensus-based process to develop a joint agreement. With its comprehensive set of 60 commitments, the agreement speaks to the root causes of conflict on multiple levels. It includes measures to improve the quality of traditional animal goods and increase access to market, with a long-term goal to make livestock herding more economically viable and establish greater financial stability across the whole herding community. It also takes a long-game approach to disputes about water resources, through commitments to build more wells, and promises a participatory monitoring program to facilitate a common understanding about mine impacts and natural resource availability over time.

The joint agreement is not yet fully implemented, and local herders know that even if done well, its measures are no guarantee against future conflicts. Recognizing that disputes between the herders and the mine are likely to arise in the future, the herders, mining company and local government also established a Tripartite Council––a freestanding body that will continue to exist for the 50 plus years of mine operation, to hear and address future grievances as they arise.

Next Up: Investment in Sharing The System and Strengthening its Reach

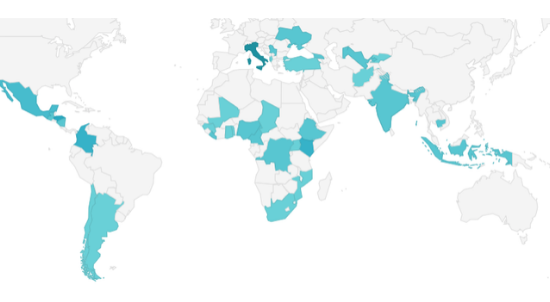

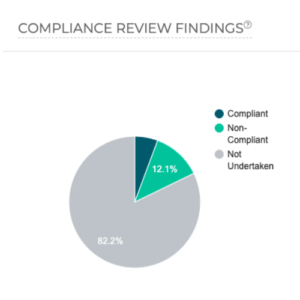

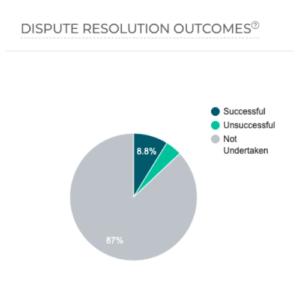

If accountability offices can be a valuable tool for communities facing conflicts with corporations, their governments, or international institutions, why aren’t they used more? There have only been around 1,300 grievances ever filed with accountability offices. Of those, only 8.8 percent of complaints led to successful dispute resolution that achieved an agreement, and only 12.1 percent of complaints led to a finding of noncompliance.

If accountability offices can be a valuable tool for communities facing conflicts with corporations, their governments, or international institutions, why aren’t they used more? There have only been around 1,300 grievances ever filed with accountability offices. Of those, only 8.8 percent of complaints led to successful dispute resolution that achieved an agreement, and only 12.1 percent of complaints led to a finding of noncompliance.

Given the promise of the system and the great need for this type of peacebuilding forum, three types of investment are required to see this promise yield more fruit.

First, communities facing conflicts related to international investment are unlikely to know that accountability offices are an option worth consideration. Organizations like ours at Accountability Counsel work to share information, and there is a critical role for the accountability offices themselves to do outreach. Outreach often requires training in local, non-national languages and in areas far from national capitals. Beyond that, however, international institutions that finance the dams, mines and agribusiness projects that give rise to conflicts have a duty to compel disclosure of accountability options through direct outreach, as well as mandating disclosure at the project level in equity and financing agreements. Companies and governments that receive international finance should be more aware of accountability offices as helpful tools to address disputes.

Second, institutions with accountability offices should invest in their peacebuilding potential. This means training and hiring professional mediators, and engaging them over the long-term throughout often lengthy processes. We have seen this done effectively by the World Bank Group’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) in our case in Mongolia and the Inter-American Development Bank’s accountability office in our case in Haiti. The CAO has also worked to foster a network of mediators and facilitators who can run their dispute resolution processes well. This takes will, budget resources, and a keen understanding of the power differential between communities and the corporations, institutions, and governments responsible for projects that impact them, and requires attention throughout a process.

Finally, there is a flood of financial flows that cause harm in local communities that do not come with commensurate opportunities to access an accountability office. Examples are any impact investing fund, all of Chinese finance, and funding flowing out from USAID. Accountability Counsel’s policy team is working on closing those accountability gaps, and as those close, peacebuilding options will open––benefiting communities and investors alike.

Investment in spreading the word about accountability offices as peacebuilding tools and investing in their power takes all of us. If you are part of a civil society organization that works with local communities facing conflicts, we need your help to share information about accountability offices with the local people who need them as a potential tool. We offer trainings and advising on accountability offices to local people and their advocates, and we invite advocates’ learning and engagement through our network called the International Advocates Working Group (IAWG).

There is no substitute for one person sitting across from another person, finding common ground, seeing one another as human, and building the trust to move through complex and challenging conflicts toward remedy and solutions. There are so few opportunities for communities to have that space––especially on equal footing with corporations, governments, and institutions. Accountability offices provide this chance, and they deserve our attention and investment.