Understanding Community Harm Part 3: Displacement

Nearly a quarter of all complaints filed to accountability offices raise issues related to displacement. We explore examples of how community complaints raising displacement issues are addressed through IAM processes, and the different outcomes and challenges communities face as a result of IAM processes.

Imagine the shock of suddenly being displaced from your home or livelihood by a project that is supposed to benefit your community or region. While some community members may eventually benefit from the project, you are left destitute and with seemingly no recourse.

Our analysis of data from the Accountability Console shows that this is a reality for many people all around the world. The Accountability Console, a comprehensive database of community complaints filed with independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs), shows that 359 of the 1,529 complaints filed in the past 25 years (23.48%) allege some form of physical or economic displacement. Given that almost 1 in 4 complainants suffer displacement as a result of internationally financed projects, this article is an attempt to dive deeper into the data to better understand the issue across development sectors.

What do we mean by displacement?

The Accountability Console considers physical displacement as relating to the loss of land or shelter, leading to physical relocation of an individual or community. Economic displacement relates to the loss of assets, or access to assets, leading to a loss of income or livelihood. Displacement can have severe negative effects on the economic, social, and cultural well-being of communities. A recent case in Uganda highlights this impact in stark detail.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kawaala community of Kampala, Uganda is facing eviction to pave the way for the construction of the World Bank-funded Lubigi drainage channel. Representatives of the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) turned up at shocked residents’ homes, placing a red “X” on many structures and explaining that they were earmarked for demolition, with no prior information about the plan. In addition to their shelter, the Kawaala community stands to lose access to their farms, which are an important source of food and income for local families. Some members also stand to lose family grave sites and other ancestral land intended for their children and their grandchildren.

Given these failures, the Kawaala community has filed a complaint about the project to the World Bank’s Inspection Panel seeking protection from the forced and unfair eviction processes, as well as meaningful consultation and participation in the design of a comprehensive and fair resettlement solution.

The experience of the Kawaala community highlights the need for a deeper understanding of displacement issues. This article examines data about complaints relating to displacement and case studies of projects to get a picture of what the most salient issues are and how they can be addressed.

Contextualizing the Data

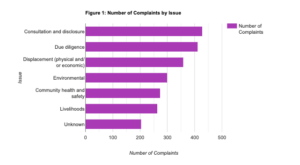

Of the types of issues tracked by the Accountability Console, complaints alleging displacement come behind only complaints about consultation and disclosure, and due diligence in frequency. As previously mentioned, 359 (23.48%) complaints allege some form of physical or economic displacement.

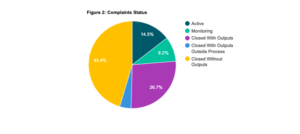

Furthermore, of the 359 complaints related to displacement, only 96 (26.7%) were closed with outputs, and 15 (4.2%) were closed with outputs outside the process. The Accountability Console defines complaints that are “closed with outputs” as complaints that completed at least one substantive phase (i.e., compliance review, dispute resolution) with a tangible output, such as a compliance report or dispute resolution agreement. 163 (45.4%) of the complaints were closed without outputs, which means that they did not complete a substantive phase.

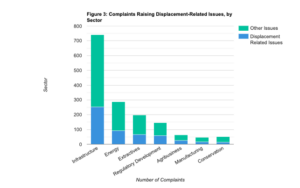

We will now take a look at the sectors with largest number of complaints alleging displacement from internationally financed projects:

Infrastructure

Infrastructure projects form the largest sector in which complaints related to economic or physical displacement are raised. These projects, like roads and public transit facilities, often encompass a large area of land and pass through inhabited regions. Further, the prevalence of infrastructure projects, and the overlap between many other sectors and infrastructure, partly explains why these projects show higher numbers of complaints. 241 of the 359 (67%) complaints related to displacement came from infrastructure projects. The Batumi Bypass Road Project in Georgia is an example of the effects infrastructure projects can have on displacement.

The Batumi Bypass Road Project, jointly financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), was a project to construct a bypass road skirting the port city of Batumi in Georgia. In October 2018, a complaint was filed against the project facilitator by a husband and wife whose land was acquired, and who believed they were paid unfair compensation. The staff at the Office of the Special Project Facilitator (OSPF), the ADB Accountability Mechanism’s dispute resolution office, determined that the complaint met the Accountability Mechanism policy criteria.

The government maintained that the compensation was fair, and refused to negotiate. They claimed that the complainant had signed a contract accepting the compensation, but the complainant alleged that he had only done so because the letter from the government along with the contract had indicated that expropriation procedures would be initiated anyway if he refused to sign the contract, and he feared that he would lose everything.

After a site visit and subsequent research by the OSPF and consultants, it was determined that the valuation of the land performed by the government was on the low side, and that an external consultant would be engaged to conduct an independent valuation. The resulting value was about 20% higher than original valuation and compensation. A negotiated settlement based on the revised figures was paid to the complainant and the complaint was resolved.

The Batumi project is just one example of how infrastructure projects can affect individuals and communities in the project area. Given the broad definition of infrastructure, there are a number of such projects undertaken around the world, often putting local communities at risk of such physical or economic displacement.

Energy

Energy projects form the second largest category of projects that have an impact on displacement, as seen by the number of complaints received by accountability mechanisms against such projects. An example of such an energy project comes from the Tata Ultra Mega Project (“Tata Mundra”) in India.

Tata Mundra is a 4,150 MW coal-fired power plant project developed by Coastal Gujarat Power Limited (CGPL), a subsidiary of Tata Power, in the Mundra region of Gujarat, India. With a total estimated cost of $4.14 billion, $450 million of which came from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in the form of a straight senior loan, the plant is located near the Gulf of Kutch and uses seawater for cooling. A complaint was brought against the plant to the IFC’s accountability mechanism, the Compliance Advisor/Ombudsman (CAO), by the Machimar Adhikar Sangharsh Sangathan (MASS – the Association for the Struggle for Fishworkers’ Rights) representing fisherpeople living in the vicinity of the project. The complaint alleged, among other things, that the fisherpeople’s seasonal settlements along the coast were overlooked during the process of land acquisition, and they now faced physical and economic displacement as a result of the project.

The CAO undertook a compliance review to determine, among other questions, if the IFC’s Performance Standard 5 (PS5), relating to land acquisition and involuntary settlement, was violated by the project. The IFC argued that PS5 should not be triggered because the fisherpeople used only temporary settlements on the land on a seasonal basis. However, the CAO found that there was enough evidence of displacement caused by the project, and concluded that the IFC had not taken the steps necessary to ensure the application of PS5.

The IFC, in turn, rejected or ignored most of CAO’s recommendations, prompting a lawsuit being filed in a United States federal court in Washington, DC, which eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019. The project is currently in the CAO monitoring phase to ensure that the IFC takes action based on the CAO’s findings.

The Tata Mundra project not only shows the impact that energy projects can have with respect to displacement, but also highlights the difficulty in developing a standard for measuring displacement. Various factors, such as access to economic resources (in this case, the waters where the fisherpeople went to fish), and the seasonality of settlements, play a role in determining whether an individual or community has been displaced economically or physically.

Extractives

The third sector that sees a large number of complaints related to displacement is the extractives sector. Extractive industry projects may include mines, drilling operations, pipelines, and the associated legal frameworks to establish and support such initiatives. An example of such a project is the Oyu Tolgoi (OT) Mining project in the Southern Gobi region of Mongolia.

OT secured $4.4 billion from 20 banks and financial institutions, including the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Insurance Guarantee Agency (MIGA), to fund an underground mine expansion. The planned expansion included excavation of more than 125 miles of tunnels that would extend almost a mile deep and would be expected to create surface subsidence approximately five square miles in size, with cliffs in excess of 65 feet tall. After this expansion, OT would be one of the largest copper mines in the world.

Public land taken for the mine would have a major impact on local herding groups. These groups follow traditional semi-nomadic herding patterns, moving their animals across large distances of publicly-owned pasture land to ensure access to enough water and pasture to sustain them in the harsh environment of the Gobi Desert. This local reality did not fit well into the Bank’s assessment of physical displacement from the mine. As a result, many herders did not receive resettlement compensation, despite losing their prime communal pastureland, an important local river and sacred spring to the mine. Since they did not personally own this land, and only used it seasonally, project documents assessed many herders as merely “economically displaced” rather than “physically displaced”.

In 2012 and 2013, local herders, representing households who live near the project site, lodged two complaints with the CAO. The first complaint raised concerns about the inadequacy of the resettlement packages offered to herders displaced by the OT Project, and the second complaint discussed the project’s impact on local water resources due to the diversion of the Undai River.

In response to the complaints, the CAO convened a dialogue process to assist the herders in reaching an agreement with the project company on these issues. The dialogue process resulted in the establishment of a Tripartite Council, with herder representatives meeting with local government and OT representatives on a bimonthly basis to work towards resolution of the CAO complaints and future community grievances related to the project.

In May 2017, after over four years of negotiations, the parties reached two agreements through the Tripartite Council’s process to resolve the herders’ complaints. With respect to displacement, the parties agreed to review past compensation provided by OT to ensure all herders who were physically or economically displaced by the project receive appropriate compensation packages. A Compensation Claims Committee was also set up to receive and review claims from herders who believe that they should have been eligible for compensation under prior compensation programs. The agreement also expanded eligibility requirements to include some herders who were unfairly excluded in the past. In recognition of the significant impacts from the mine that affected the whole local herding community, the agreements also included a package of “communal compensation”, including a herder market, slaughter line and animal laboratory to provide herders with better access to markets for their animal products.

After the CAO formally closed the case in March 2019, Accountability Counsel, which supported the communities throughout the dialogue process, undertook a review of implementation progress and published our results in a February 2019 report, From Paper to Progress: Tracking Agreements between Nomadic Herders and Mongolia’s Largest Copper Mine. The report found that at the time, only 58% of commitments had moved past initial planning stages and begun actual implementation. Some of the agreements related to displacement, especially relating to collective compensation issues like access to water and pasture overcrowding, have still not been completed, and their status can be tracked in this interactive report.

The OT project exemplifies yet another hurdle when it comes to projects that cause physical or economic displacement – the uncertainty around implementation of the agreements arising out of an accountability process. Tracking mechanisms like the Interactive Project Report are not commonplace, and a number of complainants end up having to wait for years for remedy and sometimes may end up never receiving one at all.

Moving Forward

The cases examined above highlight the need for improved policies, involvement, and accountability when it comes to projects that come with a risk of displacement. There is a distinct need for robust due diligence and strong enforcement. This can most powerfully be achieved by including strong language in the policies and standards governing the approval of projects, and procedures to ensure the IAM’s recommendations are enforced by the institution. The Tata Mundra project highlights how such failures can lead to adverse impacts on the ground. A more stringent application of Performance Standard 5, and procedures that prevent the IFC from ignoring the CAO’s recommendations, could have allowed the local fisherpeople speedier access to remedy or even the possibility of having their concerns addressed before the commencement of the project.

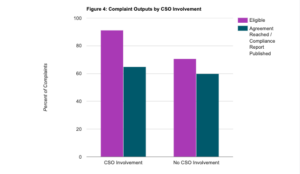

Projects that lead to displacement also tend to have government entities involved in the implementation of the project, leading to an imbalance in negotiating power with the local communities. This was highlighted in the Batumi Bypass Road Project discussed above. Here, we can see the need for IAMs to allow local and international organizations to step in as advisors or representatives for the local communities, if the communities desire this support. Our data shown below indicates that complaints about displacement that have the involvement of such organizations tend to have a higher success rate with IAMs, reinforcing the idea that such organizations bring a level of expertise that would benefit the local communities in achieving their desired outcomes.

Finally, there is also a degree of uncertainty and delay around implementation of recommendations or dispute resolution agreements arising out of the accountability process of IAMs. As noted above, transparency initiatives like Accountability Counsel’s interactive report on the Mongolia agreement are rare, and often communities lack the support and resources to ensure that the outcomes of an IAM process are properly implemented. This is yet another area where the above two suggestions could bear fruit – stronger language in financial institutions’ policies requiring management to implement the recommendations of an IAM and higher involvement of local and international organizations that can help communities ensure that the outcomes they were promised or negotiated are actually implemented in practice.

Want to read more like this? Sign up for our monthly Accountability Console newsletter here.

Photo credit: Marilia Leti, ActionAid Haiti