Peru: Oil in the Amazon

-

Overview

In 2009, Accountability Counsel worked to support the Shipibo Indigenous communities of Canaán de Cachiyacu and Nuevo Sucre in the Peruvian Amazon in their struggle to hold Maple Energy and its investors accountable for the harmful impacts of Maple’s oil operations on their land. The communities suffered seven oil spills between 2009 – 2012, leading to severe human rights and environmental abuses, including use of forced labor in one of the villages to clean up an oil spill.

The company directed local men to wade in crude oil, sometimes up to their chests, and to use rags and their bare hands to clean it up, instead of providing them with proper training, equipment, or protective gear. The spills caused widespread contamination of the villages and health impacts that resulted in sickness and death.

The World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) invested in Maple Energy in 2007, despite Maple’s lengthy record of contamination and abuse in the villages.

Accountability Counsel assisted the Shipibo communities with their complaint to the IFC’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) in April 2010. This was Accountability Counsel’s first case. The complaint addressed health and environmental impacts from the spills, harm to food security, violations of worker’s rights, abuse of Shipibo women, discrimination against the Shipibo in hiring practices, Maple’s bad faith negotiations throughout their presence in the communities, and failure to disclose information or consult local communities about the project.

The communities entered a dispute resolution process through the CAO’s Ombudsman that reached limited results due to continued bad faith on the part of the company and failure of the mediator to address power imbalances between the parties.

In May 2012, just a month after another oil spill, the CAO released its Compliance Appraisal Report, concluding that the case did not merit a full audit. This conclusion was particularly unsubstantiated given that the CAO’s compliance auditor reached his conclusions having never visited the site and never having spoken to the complainants despite their requests. Accountability Counsel believes that the Appraisal Report failed to address the egregious violations that continue to plague the communities of Canaán de Cachiyacu and Nuevo Sucre.

“For all the harm that Maple has caused, I ask that they comply with their promises. I ask this. That they comply with the promises they have made to our community.” – Raul Tuesta Berga, Nuevo Sucre, Peru

-

The Story

In 1994, Maple Energy PLC took over pipelines and wells constructed decades ago by PetroPeru and began operations in Lot 31-B. Oil wells and pipelines for this operation run through the 1,200-person Shipibo community of Canaán de Cachiyacu, located along the Rio Ucayali in Loreto, Peru. Since 2001, Maple has also operated the Pacaya oil field in Lot 31-E, which directly impacts the 300-person community of Nuevo Sucre.

Maple’s operations began in both locations without consultation with the community, without proper environmental or social impact assessment, and without payment of rent.

In 2004, after ten years of harmful impacts from Maple’s operations, the community members of Canaán gave testimony to the regional indigenous federation Organización Regional de AIDESEP Ucayali (ORAU). They described environmental and health impacts caused by contamination of soil and water from Maple’s discharged oil residues, and social harm caused by Maple’s presence, including sexual harassment and lack of respect for local culture.

In July 2005, the organization EarthRights International publicly documented Maple’s negative impacts on the communities in their Fact Finding Mission Report: Oil Impacts in the Territory of the Native Community Canaan de Cachiyacu, Peru publication.

From 2005 to 2006, the community of Canaán met with Maple repeatedly regarding disputes over demarcation of land and land value. Maple failed to comply with the majority of its promises under the resulting Community Relations Plan.

Despite the history of abusive practices and contamination, the IFC’s investment agreement with Maple was signed on 23 July, 2007. The project was assigned Category B because, according to the IFC, “a limited number of specific environmental and social impacts may result which can be avoided or mitigated by adhering to generally recognized performance standards, guidelines or design criteria.”

However, severe harm to the communities – which was not “avoided or mitigated” – did result from the project due to disregard for the IFC’s Performance Standards and guidelines.

The communities suffered seven oil spills from 2009 – 2012. Maple’s response to the most severe of the spills was to hire local indigenous villagers to clean up the oil with their bare hands, sometimes up to their chests in crude oil for days, without training, information about the harm from exposure to crude, and without any protective gear or equipment.

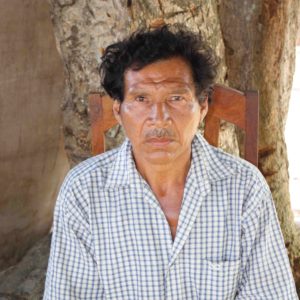

Luis Saldaña, Nuevo Sucre resident who died after cleaning up oil spilled by Maple Energy.

Maple also failed to notify villagers after the spills occurred, with children, women, and men continuing to use it as their primary water source to bathe, fish, and drink. Most residents of the villages are sick and several died after experiencing contamination from the spills. To date, Maple has refused to adequately remediate the contamination and has failed to provide adequate medical care to those directly suffering the results of Maple’s spills.

Accountability Counsel supported the communities in a dialogue process with the IFC’s accountability office, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). From the beginning, the CAO dispute resolution was plagued with problems. The mediator was switched early on and despite repeated requests, the new mediator made no effort to address the power imbalance between the Shipibo complainants and corporate oil executives as they entered the process. Furthermore, the CAO’s mediator pushed “ground rules” that prohibited the Shipibo’s advocates, including Accountability Counsel, from speaking during the dialogue table. This led to an already unequal platform for dialogue becoming a set up for failure.

Ultimately, the communities withdrew from the CAO dialogue process in protest. New spills continued to happen and Maple continued to refuse to take responsibility even during the meetings facilitated by the CAO.

The termination of negotiations came in August 2011, just a month after the death of Luis Saldaña, a resident of Nuevo Sucre who was one of the villagers forced by Maple employees to assist in the cleanup of a Maple oil spill in April 2009 without any protective equipment. Days after his death on 10 July, 2011, as Mr. Saldaña was being buried, another Maple oil spill occurred in Nuevo Sucre. Maple again hired men from the community to clean up the spill without protective equipment, training or any warnings of the health impacts of hydrocarbon exposure. Local residents also bathed in and ingested crude oil due to Maple’s failure to warn community members about the dangers and failure to provide alternative water sources.

After the dispute resolution process failed, Accountability Counsel supported the complainants from Nuevo Sucre and Canaán as they reiterated their request that the CAO complete a compliance audit. While the CAO declined to conduct a full audit, given the nearly full staff-turnover at the CAO since this time, we do not believe this would be the result these communities would get today.

After the CAO process came to an end, the communities again peacefully occupied the oil wells in September 2012. Demonstrating the business case for functional accountability office processes, Maple claimed that “the action has slowed its production of low sulphur crude oil from the Maquia oil field near the Ucayali River in Loreto, Peru’s northernmost region.”

Learn more about the CAO complaint process in this case and our impact.

Shipibo man cleaning up an oil spill with his bare hands in a creek used for drinking.

Case Partners

Organización Regional AIDESEP Ucayali: a regional chapter of the Asociación Interétnica de Desrrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP) established in 1980 to defend and promote the rights of the indigenous peoples of the Peruvian Amazon.

Federacion de Comunidades Nativas del Bajo Ucayali: a member of AIDESEP that represents Conibo and Shipibo indigenous organizations in Peru.

International Accountability Project: a nonprofit that challenges destructive development projects that uproot and impoverish millions of people across the Global South.

Derecho Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: a Peruvian nonprofit organization dedicated to the sustainable development of the country.

EarthRights International: a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization that combines the power of law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment, which it defines as “earth rights.”

-

The Case

-

May 2012

The CAO released its Appraisal Report (also available in Spanish), concluding that the case did not merit a full audit.

The appraisal report failed to address the egregious violations that continue to plague the communities of Canaán de Cachiyacu and Nuevo Sucre.

In one of the starkest cases of abuse by an oil company, the IFC stood by as an active investor in violation of their own Performance Standards. When offered an opportunity to take responsibility and correct these violations through a complaint to the IFC’s CAO, the CAO abandoned its mission, confusing an attempt to comply with the standards with actual compliance. This failure to engage with the facts of the complaint and failure to conduct an audit worsened social and environmental outcomes in the affected communities instead of contributing to better outcomes, which is the CAO’s mandate.

-

Apr 2012

On April 23, 2012, the community of Canaán de Cachiyacu suffered another oil spill in the Cachiyacu tributary caused by IFC funded Maple Energy plc. This letter to Henrik Linders at the CAO on the following day requested that the CAO immediately visit the site of the latest spill and conduct an investigation of the IFC’s continuing role in these environmental and human disasters.

Mr. Linders did not visit the site.

-

Oct 2011

The CAO issued its conclusion report (also available in Spanish) summarizing the CAO’s perspective on the Ombudsman process.

-

Sep 2011

The communities of Nuevo Sucre and Canaán sent an open letter (also available in Spanish) to the CAO regarding completion of the dispute resolution process. The communities’ decision to withdraw cited Maple Energy’s bad faith conduct in the negotiations and the coercive nature of the negotiations that prohibited the communities’ selected advisors, including the indigenous federations ORAU and FECONBU and Accountability Counsel, from speaking during negotiations.

-

Sep 2011

The Peruvian Government’s multi-sectoral commission of vice-ministers reached an official agreement (original Spanish version) with the indigenous communities of Nuevo Sucre and Canaán that confirms Maple Energy’s contamination of Shipibo land and waterways.

-

Aug 2011

The Government of Peru (Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú) reached an agreement (original Spanish version) with the communities to form a multi-sectoral commission to investigate the spills by Maple Energy on Shipibo territory in Nuevo Sucre and Canaán.

-

Aug 2011

Because Maple Energy (a) continued to knowingly expose villagers to crude oil even during the negotiations, (b) failed to remediate or provide health care after the July 2011 spill, and (c) refused even to pay for studies regarding the extent of the clean up and health care required, the communities withdrew from the CAO dialogue process in August 2011.

-

Jul 2011

-

Jul 2011

Children bathing in a creek observed an oil spill while the community was in mourning over the death of community elder Luis Saldaña. The company had men from Nuevo Sucre clean up the spill with no training, protective gear, or information about the impacts of exposure to crude oil.

Women and children continued to use the water during the spill because it was their primary water source. Despite the community complaint to the CAO about the same atrocities in 2009, Maple Energy provided no food or water to the community members who continued to rely on the contaminated waterway.

-

Jul 2011

Partner organization Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (DAR) published a report (only available in Spanish) about hydrocarbon activity in the Shipibo communities.

-

Apr 2011

The communities and Maple Engery entered a dialogue process mediated by the CAO’s consultant, Antonio Bernales.

-

Jan 2011

The CAO issued its Stakeholder Assessment Report (also available in Spanish) that set out steps for entering into a mediated dialogue process.

-

Jun 2010

The CAO conducted an assessment visit to the communities with professional mediator Juan Dumas to determine whether a dialogue process could begin through the CAO’s ombudsman function. The parties expressed interest in pursuing a dialogue process.

-

Apr 2010

-

Nov 2009

Accountability Counsel, International Accountability Project, Amazon Watch, and Peru-based Racimos submitted a letter to Lance Crist, the IFC’s Executive Vice President for Oil and Gas, about the project.

The IFC sent a letter in reply, committing to “review further the background of these incidents and the adequacy and appropriateness of the company’s response.”

After this correspondence, the communities saw no change in Maple’s practices or action by the IFC and the oil spills continued.

-

-

Impact

AC’s Natalie Bridgeman Fields in a training in Nuevo Sucre, Peru

Accountability Counsel’s impact in the Maple Energy case was the documentation of severe corporate abuse by an oil company in remote indigenous villages in Peru. Our impact was the gathering and publishing of evidence of the role of the World Bank Group’s IFC in financing the abuse. Our impact was greater awareness of the abuse due to media coverage of the spills and the community response.

Nonetheless, our impact was substantially hampered due to unprofessional treatment of the case by the IFC’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) during the 2010-2012 time period. The mediation that reinforced unequal power dynamics, coupled with the failure to conduct a compliance audit meant that the CAO derogated its mission.

The troubling results from the CAO complaint process led Accountability Counsel to accompany the communities as they worked to employ additional strategies to hold Maple accountable for abuse. Shortly after the CAO process completed, our work facilitated a high-level Peruvian Government delegations investigation visit to the region that confirmed Maple Energy’s role in causing the harmful environmental and health impacts in the area.

We also began work to advocate with accountability offices to recognize and better address the power imbalance between the parties. We note that has been nearly full turn-over with the decision-makers at the CAO since this case. We don’t believe the current CAO staff would have addressed this case in the same way.

Finally, this case is evidence of the business case for entering dispute resolution in good faith and investing in strong accountability offices. After the CAO process failed, the communities continued to suffer from oil spills. The communities again peacefully occupied the oil wells in September 2012. Maple claimed that “the action has slowed its production of low sulphur crude oil from the Maquia oil field near the Ucayali River in Loreto, Peru’s northernmost region.”

-

Case Media

Videos

Media Coverage

- 15 April 2015 How the World Bank is Financing Environmental Destruction By Ben Hallman & Roxana Olivera, HuffPost & the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Press Releases

Photos

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Village of Nuevo Sucre in the Peruvian Amazon demanding their rights

Village of Nuevo Sucre in the Peruvian Amazon demanding their rights -