What happens when development goes wrong in the MENA? Part 1

Introduction

Independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs) are often the last and only resort available to communities in the face of harm from development projects. They play an important role in ensuring that communities have a voice in development decisions that impact them. When they function well, IAMs can provide substantive and meaningful remedy to communities alleging harm from IFI-sponsored projects. However, the efficacy of these processes ranges widely and depends on a number of factors, including the robustness of the complaint that is submitted, the resources and level of organization of complainant communities, the presence and extent of civil society organization (CSO) support, and the location of the project. Other structural factors such as the capability of the IAM to manage the process fairly and effectively, the willingness of the bank to engage with the IAM process, and the threat of retaliation and violence faced by complainants also influence the efficacy of IAM processes.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has the fewest absolute number of complaints out of any region globally and the second lowest rate of complaints addressed through a compliance review or dispute resolution. In an effort to understand why this trend is happening, we conducted an analysis of all MENA complaints filed to IAMs and projects financed by IFIs. We also consulted with groups who have filed complaints and with representatives from IAMs that have handled complaints in the MENA. In doing so, we discovered a number of barriers to accountability in the MENA which appear to be limiting the number of complaints filed and the outputs from IAM processes. These include significant experiences of and fear of retaliation, suppression of organized civil society, limitations on resources and knowledge of navigating IAM processes, and lack of bank and IAM leverage. Our upcoming report, Our Last and Only Resort, set to launch on September 12, further details these limitations. Below, we take a look at the complaint and project data in depth, and detail our analysis that has informed our key findings and recommendations in the report.

The Data

Low Complaint Volume

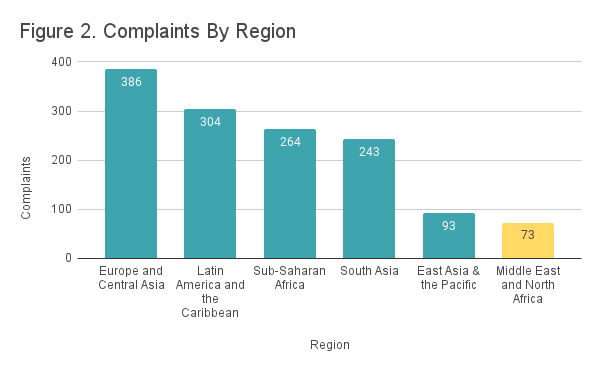

The MENA has the fewest absolute number of complaints out of any region globally. Seventy-three complaints have been filed in MENA countries, significantly less than the global average of 195 complaints per region.

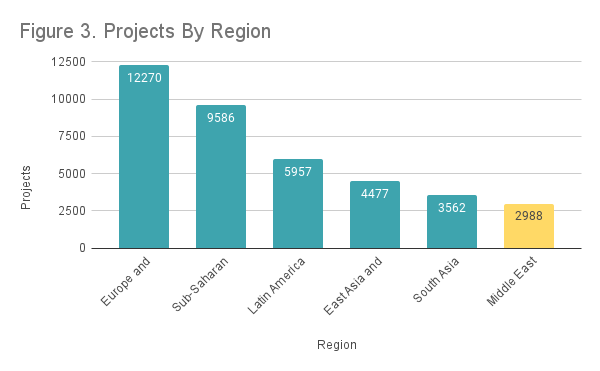

One theory as to why there are so few complaints filed in the MENA relative to other regions is that there are also fewer projects about which to complain. A regional breakdown of total IFI-financed projects does in fact show a very similar distribution:

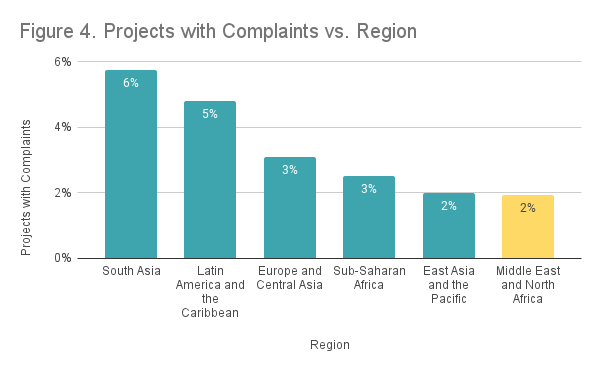

But even accounting for the reduced absolute number of projects, the percentage of projects that have complaints remains lower than any other region:

The global average rate of complaints filed per project is 3.2% (1,258 projects with complaints out of 38,840 estimated projects).* South Asia has the highest rate of complaints filed per project at 5.8% (205/3,562). The MENA has the lowest rate of complaints filed per project at 1.9% (58/2,988), though East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa also have below-average proportions of projects with complaints, at 2.0% (89/4,477) and 2.5% (240/9,586) respectively.

A low rate of complaints filed per project has a number of potential implications worth investigating. One theory is that IFIs are focusing on lower risk investments in the MENA, but this is also unlikely to be the case: the proportion of high risk “Category A” projects (11%) is in fact slightly higher than the global average (9%).**

Another possible explanation is that harm from development projects is not occurring, or is less likely to occur, because social and environmental safeguards are better enforced and better adhered to, thus leading to fewer instances of harm. It’s also possible that the MENA has favorable alternatives to the IAM complaint system that are available for raising and addressing harm, such as effective court processes. However, even a cursory regional analysis eliminates both these possibilities; harm is clearly occurring and few alternative systems of recourse exist.

A more troubling and yet more plausible possibility is that harm is still occurring, but is not being raised. This could be due to factors such as barriers to accessibility, limited knowledge of the IAM complaint system, or a weakened civil society that is unwilling or unable to raise concerns about harm for social and political reasons, including a high risk or fear of retaliation. It is notable that the MENA is the only region without a regional bank and associated IAM, which could be influencing the accessibility of IAMs as an effective method for recourse.*** In an effort to understand which of these theories may help explain both the low absolute and relative complaint volumes observed in the MENA, we have explored these potential implications through our qualitative research with CSOs that have experience filing complaints in the MENA, representatives of IAMs who have experience handling MENA complaints, and existing literature surrounding these topics.

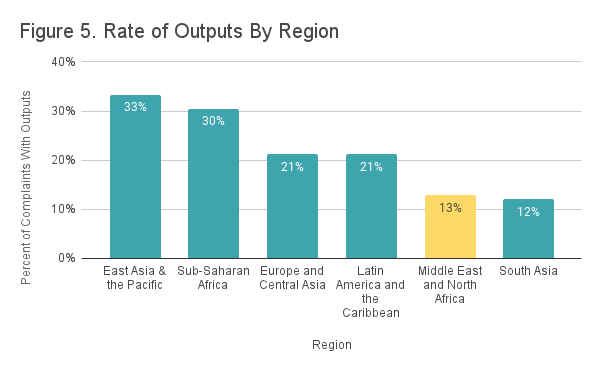

Low Rate of Outputs

The rate of complaints reaching outputs from the complaint process is low everywhere. Globally, fewer than one in five complaints (18.5%) close with an agreement or a published compliance report. MENA complaints face the second lowest rate of outputs by region: only 13% of complaints filed manage to reach an output from this process:

Significant bottlenecks in the IAM process exist, inhibiting complainants from reaching an output (see our previous newsletter article “The Eligibility Bottleneck” for more information). A further look at particular stages of the IAM complaint process can help determine why the rate of outputs in the MENA is so low.

Most IAMs have two preliminary stages, registration and eligibility, that complaints must pass through in order to advance to a substantive phase of the complaint process. Specific registration and eligibility criteria vary by IAM and more than half of all complaints fail to pass through these preliminary stages. (To view and compare criteria by IAM, visit our benchmarking form.)

A regional breakdown shows no significant variation in MENA eligibility rates (46.3%) from the global average (41.1%).

Looking one step further, we start to see significant barriers for MENA complaints to advance past an “eligible” status to actually enter a substantive phase of the complaint process: dispute resolution or compliance review.

This is a startling and often overlooked deficit (our previous newsletter article “Shadow Eligibility Barriers” explores this further). It is generally understood that ineligibility determinations keep many complainants from effectively accessing these processes, and that complainants that successfully enter a substantive stage do not always exit these processes with outputs.**** However, the data shows an important intermediate dropoff point, where eligible complaints are not afforded the opportunity to even enter a substantive stage at all. In the MENA, one in three eligible complaints never reaches a substantive stage, the lowest engagement rate of any region in the world. Barriers to eligible complaints entering a substantive stage could be related to particular IAM policies (like requiring Board approval) that prevent substantive stages from being made available, project companies or governments refusing to participate in dispute resolutions, or the mechanism itself deciding that further involvement is unnecessary.

In addition to having the lowest rate of eligible complaints reaching a substantive stage, even when a dispute resolution or compliance review is initiated, the rate of outputs from these stages in the MENA remains disproportionately low. On average globally, 69% of complaints that reach a dispute resolution stage produce a public agreement, compared to 57% in the MENA. For compliance reviews, the comparison is even more stark: globally 82% of all compliance reviews result in a public compliance report, and 83% of these reports have findings of non-compliance. But in the MENA only 33% of compliance reviews produce a report, with a 66% rate of non-compliance found.

A low rate of outputs from the complaints process has a number of potential implications warranting further attention. These include variance in the ways that different IAMs handle complaints, as well as variance in the ways that complaints are handled within a given IAM. It could also be related to variability in the types of issues raised or the processes undertaken, including the types of actors involved, the power dynamics at play throughout the complaints process, or the engagement of civil society and other actors supporting the complaints process.

Investigating Implications of the Data

The complaint and project data above expose a number of important implications about regional differences in IAM complaint processes across the world. In order to better understand how these differences are impacting the lives and experiences of communities impacted by development projects in the MENA, we conducted interviews with nearly a dozen groups who have filed complaints to IAMs in the region, and talked with representatives from four IAMs that have handled complaints in the MENA. Our upcoming report details the findings from these qualitative interviews, and discusses recommendations for how IAMs and IFIs can address these gaps in accountability.

We found that there are a number of factors within the scope of IAMs and IFIs that are limiting both access and efficacy of complaints in the region, as well as other broader structural, governance, and social issues that can be addressed and mitigated through thoughtful and nuanced adjustments to the management of complaints. The learnings from this research can also support impacted communities and their advocates to engage with the IAM system more effectively with a greater likelihood of success. Our report will be available online at (LastAndOnlyResort.com) on September 12.

To be continued! Part 2 will follow next month.

ENDNOTES

* Though data exists for 1,605 complaints as of June 2022, 242 complaints have no data on location, and an additional 105 complaints were filed about projects with a previous complaint.

** World Bank project data, including projects from 1947 through 2022, accessed June 2022. https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/projects-list.

*** Where regional banks and IAMs exist, they receive the majority of complaints filed in that region. The absence of a regional bank and associated IAM means that the majority of complaints filed in the MENA are to global (World Bank, International Finance Corporation) or European (European Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) institutions. Further information on regional complaints by IAM is available in Appendix B.

**** C. Daniel, K. Genovese, M. van Huijstee & S. Singh (Eds.), 2016. “Glass Half Full? The State of Accountability in Development Finance.” Amsterdam: SOMO.

This article was originally published in the Accountability Console Newsletter, where AC’s Research team shares research and insights from the world’s most comprehensive database of Independent Accountability Mechanism (IAM) complaints, the Accountability Console. Click here if you would like to subscribe to the monthly Console Newsletter.