Analyzing Environmental Impacts Across Development Sectors

An analysis of complaints filed to all IAMs shows how even well-designed projects intending to alleviate poverty can lead to adverse impacts on the environment, biodiversity, access to water, and increased pollution. A critical way to understand and address unintended environmental harms is to hear from communities living near and working at project sites.

Even well-designed projects intending to alleviate poverty can have unintended negative impacts. At times, International Financial Institution (IFI) investment projects lead to adverse impacts on the environment, biodiversity, access to water, and increased pollution (“environment-related harms”). A critical way to understand and address unintended environmental harms is to hear from communities living near and working at project sites. In this regard, IFIs should value lessons learned from their independent accountability mechanisms (IAMs).

IAMs are forums through which individuals can raise concerns when they face actual or potential harm as a result of a public or private sector project, investment, or business-related activity. They operate independently of the institution in which they are housed but report to the institution’s highest level of leadership and rely on the institution for funding. When they function well, IAMs can be efficient, flexible, and cost-effective means of addressing and resolving disputes.

Below is an analysis of complaints filed to all IAMs that allege environment-related harms. After showing a snapshot of complaints to all IAMs that allege environment-related harms, this paper focuses on alleged environment-related harms regarding World Bank projects in particular. Data in this paper is from the Accountability Console, which is the world’s most comprehensive database of community complaints filed with independent accountability mechanisms about the impacts of internationally financed projects. The paper also provides summaries of specific cases, from the World Bank’s Inspection Panel and from other IAMs, that provide more qualitative context of environment-related issues caused by development projects across sectors.

Environment-related Harms Pervasive in Complaints submitted to IAMs

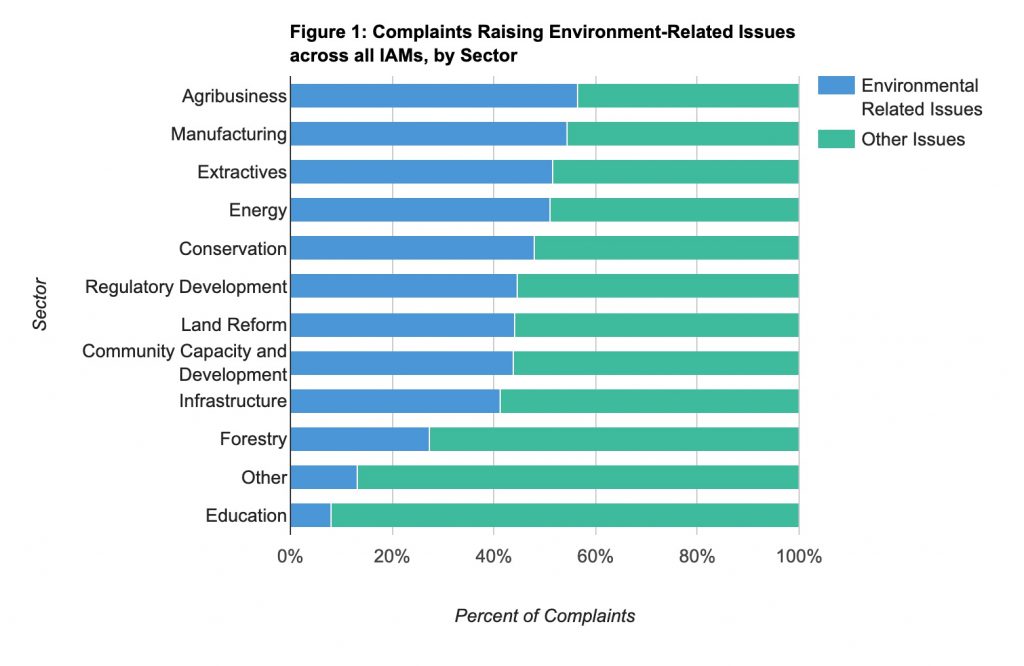

AC has tracked all complaints logged with every IAM over the last 25 years; in that time, there have been 1,395 total complaints, 484 of which contain accusations of environment-related harms. In other words, complaints alleging environmental harm represent a third (35%) of this entire dataset. These complaints arise from projects around the world– particularly in Africa, East Asia, Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia. Furthermore, our analysis indicates that environment-related harms are alleged across all development sectors (see Figure 1).

Environment-related Harms Across Development Sectors at the World Bank and other IFIs

Complaints filed to the World Bank’s IAM, the Inspection Panel, also demonstrate that environment-related issues are raised for projects in all sectors. Some sectors are not ones in which environmental risks would be readily assumed, such as education or community capacity building, and yet, even in these sectors, communities identify risks the projects pose for the local environment. Even with conservation projects, ostensibly designed to help the environment, communities raised concerns about environmental damage.

In an effort to prevent and minimize environmental harms in projects, the World Bank has undertaken systemic internal reforms. It began by producing its Environment Strategy (2012), Biodiversity Roadmap (2014), and Forest Action Plan (2016) to ensure that it addresses climate change and sustainability. As the World Bank has initiated sustainability efforts, communities affected by World Bank projects in all sectors continue to raise the potential of environment-related harms across all sectors to the Inspection Panel, the World Bank’s IAM. Figure 3 shows environment-related issues raised in World Bank Inspection Panel Complaints since 2010, by sector.

The following sections focus on a few development sectors in particular, namely the regulatory development sector, infrastructure development sector, community capacity and development sector, and manufacturing sector, and provide insight on environment-related risks posed and harms caused by certain projects.

Extractive Sector

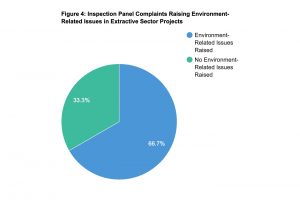

Extractive Sector projects must have environmentally sound management plans to curb potential or actual human rights and environmental impacts. Extractive industry projects may include mines, drilling operations, pipelines, and the associated legal frameworks to establish and support such initiatives. Of the extractive sector project complaints received by the Inspection Panel, 67% of complaints allege environment-related harms. These complaints arise from projects across eight countries.

Maple Energy PLC has a long history of human rights and environmental impacts in Peru, extending from 1994. Maple Energy began managing oil pipelines and wells that run across the Shipibo and Nuevo Sucre communities without consultation with the community members, without proper environmental or social impact assessment, and payment of rent. In 2005, EarthRights International documented the horrendous impacts Maple’s had on the community that began a string of disputes between affected communities and Maple.

Despite the ongoing documentation of adverse practices by Maple, the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) invested in Maple Energy in 2007. IFC rated Maple’s project investment a Category B because it found a “limited number of specific environmental and social impacts may result which can be avoided or mitigated by adhering to generally recognized performance standards, guidelines or design criteria.” As abusive practices continued to mount, affected communities, supported by Accountability Counsel and other partners, filed a complaint to the IFC’s IAM, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO). The complaint outlined the IFC’s failure to properly categorize the project’s environmental risks that had already produced mounting effects on the environment, health, and food security after its three major oil spills.

To resolve their concerns, community members agreed to pursue a collaborative dispute resolution process with Maple and moderated by the CAO. Early on, the Shipibo communities and advocates faced insurmountable problems with the dispute resolution and decided to withdraw from the process. After the dispute resolution process was closed, the CAO completed a Compliance Appraisal Report, concluding that the case did not merit a full audit.

Accountability Counsel disagreed with the CAO’s decision not to undertake a compliance review. The CAO did not consider the many failures by Maple in part because the CAO’s compliance auditor never visited the project site, nor did they speak to the complainants. Canaán de Cachiyacu and Nuevo Sucre’s communities endured egregious violations of environmental and human rights that could have been prevented if the IFC would have taken adequate due diligence before investing in Maple.

Although the CAO did not undertake a compliance audit, environmental harms from extractive projects exist. In an attempt to underscore the importance of recognizing the inherent threats posed by extractive sector projects, the UN Special Rapporteur released a report emphasizing current hazardous extraction methods and waste management practices undermining human and environmental rights. To emphasize the critical need to reevaluate the roles and responsibilities of extractive sector activities, the Special Rapporteur cited a case involving Maple energy’s operations in Peru as an example of an extractives project with far-reaching consequences, harming biodiversity and causing damages to human lives.

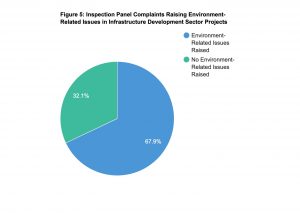

Infrastructure Development Sector

Infrastructure development sector projects have also proven to cause incredible environment-related impacts in communities in complaints received by the Inspection Panel (See Figure 5). The infrastructure development sector includes construction or improvement of large structures, facilities, or public works projects, including roads and other transportation projects. Other infrastructure projects include sanitation and water treatment facilities, power plants, and industrial facilities. Complaints arise from infrastructure development sector projects in thirty-one countries. Infrastructure sector project complaints to the Inspection Panel specifically outline, among other harms: sea dumping of liquid waste, affecting the health, fishing industry, and tourist industry of local areas; deletion of forests and wetland, adversely affecting migratory birds and small mammals which inhabit the area; and irreversible harm to historical and ecological sites.

The Eskom Investment Support Project in South Africa, financed by the World Bank, is an example of an infrastructure development sector project that had environment-related issues. The Project included a 4,800 MW coal-fired power plant near Lephalale in the Waterberg District, Limpopo Province, and associated infrastructure developments for renewable energy generation sources. In 2010, groundWork and Earthlife Africa submitted a complaint to the World Bank Inspection Panel on behalf of community members living in the project area. Along with threatening villagers’ access to drinking water and disrupting Indigenous infrastructure like reducing the availability of traditional medicines, the complaint also outlined how the Eskom Investment Support Project would ultimately augment the systemic inequalities present in South Africa. The independent review conducted by the Inspection Panel ultimately confirmed environmental impacts produced by the Project including: significant water consumption; emission of gases and particulates causing increased health problems; and limited institutional capacity to cope with the public and social infrastructure and environmental management.

Manufacturing Sector

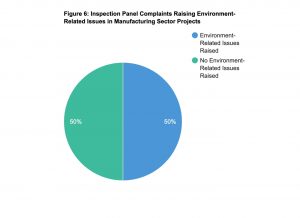

Manufacturing sector projects frequently relate to large scale production of goods, including production capacity and infrastructure. At times, these types of projects have led to air pollutant emissions being released into the air and water pollution, increasing health and environmental damages.

Of the two manufacturing sector complaints received by the Inspection Panel, one complaint alleged environment-related harms. The complaint alleges environmental and social impacts caused by the Export Development Project. The World Bank Inspection Panel, however, did not register the complaint as under the Panel’s eligibility criteria, the Panel may not investigate Projects for which the loan has been closed or more than 95% disbursed. Across all IAMs, the rate of 54% of complaints relating to manufacturing sector projects allege environment-related issues (See Figure 2).

Across all IAMs, the rate of 54% of complaints relating to manufacturing sector projects allege environment-related issues (See Figure 2). An example illustrating communities seeking redress for environment-related harm in an extractive and manufacturing sector project is the Mozal II project, co-financed by the European Investment Bank (EIB), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG), and Proparco. The Mozal II project was an extension of the existing Mozal aluminium smelter for which the EIB provided a direct loan to Mozal, a joint venture of the BHP Billiton Group, and to the Republic of Mozambique for minority equity participation in 1997. The Mozal II project sought to expand the construction and operation of the existing Mozal aluminum smelter.

In 2010, Mozal was impacted by an unanticipated corrosion that forced them to rebuild a Fume Treatment Center (FCT) to treat fumes from the anode bake furnaces. As a result of the building of the FCT, Mozal needed to go into bypass mode. This resulted in the emission from the bank furnaces being released directly into the atmosphere via the existing stacks. In 2010, coalition of Mozambican NGOs (Justiça Ambiental, Livaningo, Liga Moçambicana dos Direitos Humanos, Centro Terra Viva, Kulima and Centro de Integridade Pública) filed a complaint to a number of IAMs including the EIB Complaints Mechanism (EIB-CM), the Office of the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO) for IFC & MIGA and the OECD UK National Contact Point.

The complaint raised issues concerning air emissions and risks these could pose to human health and the environment and lack of access to and disclosure of information when the decision was made that Mozal would operate under bypass for six months during the rehabilitation of gas and smoke treatment centers.

Initially, the EIB-CM, in collaboration with the CAO, performed an initial assessment to better understand the complaintaints’ allegations. After the assessment, the CAO pursued a mediation process and the EIB-CM conducted a compliance review. After many months of attempting to settle a successful negotiation, there were no final agreements reached at the end, and the NGO coalition requested that the complaint be referred to CAO’s compliance review.

After the completion of the compliance review, the EIB-CM found that there was room for improvement regarding the management and monitoring of emissions to the environment.

Moreover, the audit conducted by the CAO concluded that IFC’s supervision of E&S risks associated with the failure of the FTCs at Mozal fell short of that required by IFC policies and standards. The UK NCP concluded that BHB BIlliton acted in accordance with 2020 version of the OECD Guidelines and established and maintained an environmental management system appropriate to the enterprise.

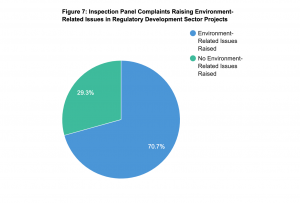

Regulatory Development Sector

The Regulatory development sector is a leading sector of alleged environment-related complaints received by the World Bank Inspection Panel (See Figure 7). These projects relate specifically to development or reform of legal frameworks, including laws and regulations.

Of the regulatory development sector complaints received by the Inspection Panel, 71% of complaints allege environment-related harms. These complaints arise from projects across seventeen countries.

An example of communities seeking redress for environment-related harm in the regulatory development sector is a complaint filed about the Transitional Support for Economic Recovery Credit (TSERO) and the Emergency Economic and Social Reunification Support Project (EESRSP) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2005, Indigenous Pygmy organizations and Pygmy support organizations in the Democratic Republic of Congo filed a complaint to the World Bank Inspection Panel regarding the TSERO and the EESRSP funded by the World Bank. The EESRSP and the TSERO projects were supposed to focus on restoring effective institutions in the forestry sector by bringing a new Forestry Code into practice, addressing the problem of illegal logging. Instead, the projects were characterized by serious environmental harms, such as the violation of the right of the Indigenous Pygmy community to occupy their land, leading to their inability to maintain and manage their ancestral land (including forests) and the facilitation of increased levels of industrial forest exploitation.

In particular, the complaint focuses on how they have been harmed or will be harmed by the activities supported by the EESRSP. The EESRSP has five components: (i) Balance of Payments Support (ii) Institutional Strengthening; (iii) Infrastructure Rehabilitation; (iv) Urban Rehabilitation; (v) Community Empowerment. The complaint focused on Component 2 which has the objective of helping to restore effective institutions in the forestry sector in DRC province, improve local governance over natural resources, bring the new DRC Forest Code into practice, and address the problem of illegal logging.

The World Bank Inspection Panel released its independent review of the projects, which found that World Bank Management failed to prepare an environmental assessment for Component 2 of the Project and undertake a comprehensive analysis demonstrating that the overall benefits from the project substantially outweigh the environmental costs, as required by Operational Policy 4.01 Environmental Assessment and 4.04 Natural Habitats. Ultimately, the Panel explicitly noted that, in its present form, the Project may not contribute significantly to alleviate poverty and may indeed contribute to adverse impacts on poverty to the extent that logging practices are unsustainable.

Fortunately, the management of the EESRSP and TSERO projects provided progress reports throughout the implementation of their reparative action plan. In fact, of the 41 complaints arising from regulatory sector projects and alleging environment-related issues, the TSERO and EESRSP complaint is one of the 11 (27%) regulatory development sector project complaints alleging environment-related issues that were closed with outputs achieved. Unfortunately, the majority (24 complaints or 58.5%) of the regulatory development sector project complaints alleging environment-related issues achieve no outputs.

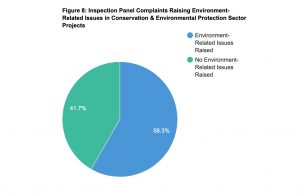

Conservation and Environmental Protection

Conservation and environmental protection projects seek to preserve or manage the natural environment, establish legal frameworks regarding ecological protection or pollution, and target carbon sequestration or other climate change mitigation activities. Although the objective of conservation and environmental protection projects seek to earn positive and sustained results on the environment, if poorly designed or implemented, these projects can result in environmental harm. For example, many of these projects fail to consult with the Indigenous communities and other primary stewards of the environment, leading to irreversible and consequential harms. Of the conservation and environmental protection sector complaints received by the Inspection Panel, 58% of complaints allege environment-related harms. These complaints arise from projects across six countries.

In southeast Myanmar’s Tanintharyi region, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) is implementing the $21 million “Ridge to Reef” project through funds from the Global Environment Facility (GEF), with support from the Myanmar government, Flora and Fauna International, and the Smithsonian Institute. The Ridge to Reef project is a prime example of how conservation efforts can threaten biodiversity and produce unintended consequences that inflict harm across those living in the project areas.

The Government of Myanmar has faced severe challenges in managing the biodiversity in SouthEast Myanmar’s Tanintharyi Region, having endured a 70-year civil war. As a solution, the Ridge to Reef project was introduced to designate 3.5 million acres in the Tanintharyi region as a government protected area, including forest, coastal, and marine areas. Instead of adhering to the project goals and objectives of conservation, the Government of Myanmar has allowed rampant logging and granted large concessions to commercial actors, including palm oil plantation companies.

Accountability Counsel is supporting Conservation Alliance Tanawthari, a coalition of community organizations in Myanmar’s Tanintharyi region who have raised concerns about the project. The complaint filed to the United Nations Development Program’s Social and Environmental Compliance Unit (SECU) highlighted concerns regarding violations of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), threatened livelihoods of those living in and around the project site, and jeopardizing community-driven initiatives to protect territories, forests, and resources in the project area. After finding the complaint eligible, SECU conducted the first of two investigation visits to communities from July 18-20, 2019 and suspended its second investigation visit scheduled in February 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. UNDP Myanmar has suspended the project until the investigation is complete. A complete investigation surrounding the complaint is expected in 2021.

Conclusion & More to Be Done

The well-documented pervasiveness of environmental impacts in IAM complaints across development sectors means that IFIs need to approach all projects with a view to potential environmental harm that may result. Not only can IFIs undertake efforts to prevent and mitigate environmental harms, but they can also seek to measure environmental impacts across all sectors. One component of effectively understanding and measuring environmental risks and impacts is hearing directly from communities. In this regard, IFIs should champion their IAMs as a critical way for communities to raise concerns about project risks and harms, and therefore a vital mechanism to ensure projects’ success.

In addition, IFIs should commit to ensuring that IAM processes are strong and effective enough to fully investigate and address environmental harms alleged by communities. First, some complaints raising valid concerns of human and environmental harms are barred from proceeding due to overly restrictive eligibility criteria. Second, even complaints that are eligible too rarely result in tangible outputs such as a publicly disclosed compliance report or dispute resolution settlement report. For example, of the 484 complaints alleging environment-related issues across all IAMs, only 20.2% (98) were closed with outputs achieved via the relevant IAM, while 14.3% (69) remain active and 8.5% (41) are being monitored And even when there are outputs, it is the IFIs’ responsibility to ensure adequate remedy. While it is beyond the scope of this analysis to investigate what remedy was ultimately achieved from these IAM complaints, past reports have shown that even in cases that produce outputs, real remedy does not always follow.

This article was originally published in the Accountability Console Newsletter, where AC’s Research team shares research and insights from the world’s most comprehensive database of Independent Accountability Mechanism (IAM) complaints, the Accountability Console. Click here if you would like to subscribe to the monthly Console Newsletter.